The very first Habeas Corpus writ filed in India, after Emergency period was, Prof. Eacharavaryar vs Govt of Kerala. Verdict of the suit toppled then State Government, resulted in resignation of CM, and is still the exemplar of Police brutality and Human Rights violation. This book is an autobiographical account by T.V. Echaravaryar (Eswara Warrier) himself, of his relentless and lonely legal struggle for justice and truth behind the unaccounted disappearance of his son P. Rajan in Police custody.

1975 June 25 midnight to 1977 March 21 was one of the darkest period in modern Indian history when democracy was eclipsed by Prime Minister’s authority to rule by decree. Popularly known as Emergency period or just Emergency, this brief cameo of dictatorship was notorious for curbing of civil liberties, police brutality, imprisonment of political opponents and press censorship. Something present generation of mine cannot really think of, or have a reference on. Invocation of Emergency was Mrs. Gandhi‘s antibody against then prevailing political and civic unrest; which in turn was the byproduct of increasing government intervention in judiciary and dissolution of State legislatures. A lot of benevolent reasons have been brought up over time to justify the Emergency from 1973 oil crisis to split in Congress to fallacy of Raj Narain case. But every single one of them falls short when weighed against the violation of civil rights by police activism; a gritty dystopian scenario where fundamental rights of citizens were no longer justiciable nor defendable by Supreme Court.

Naxalism was one of the major target for police crackdown during Emergency. Originating from a small village in WB, Naxalbari, after the Communist split of 1967, the radical movement for tribal autonomy(obvious over simplification of the complex reasons here) gained momentum along the scheduled belt through their reactionary ideas and violent methods. Naxalite movement is still a controversial topic in internal geopolitics which puts sympathizers in a moral tug of war. In rural Kerala, the peak of this activism, during Emergency, involved direct attacks on police stations, which in return witnessed violent retaliations and often vengeance under the misnomer of ‘naxalism’. Police by State backing took full advantage of suspension of civil liberties and MISA (infamously expanded as Maintenance of Indira and Sanjay Act) act, a then civic version of current AFSPA, and went around raiding suspects for interrogation. P. Rajan, a student of Regional Engineering College, Calicut (Now known as NIT Calicut) was arrested by Kerala Police in one of those raids, citing alleged Naxal association and was brutally tortured in custody, and was killed. The interrogation happened in Kakkayam camp, under DIG Jayaram Padikkal, and was said to have employed the extreme torture practice of ‘uruttal’ (rolling); Rajan’s body was disposed off and was never recovered, and by the classic book excuse of no body-no conviction, DIG later managed considerable legal escape.

Prof. Warrier was living his retirement in Cochin when Rajan got arrested; he immediately filed petition asking for his son’s whereabouts and objectives behind the arrest. He made enquiries after enquiries to police officers and to authorities, with all references he could garner, for details behind his son’s disappearance. Later, on learning that the arrest was directed by DIG, Crime Branch, he personally met K.Karunakaran, then Home Minister of State and escalated his petitions to Home Secretary, but none of these efforts were acknowledged. It is extremely difficult to read through his words, filled with sorrow, helplessness and uncertainty. Above all there was the ‘naxal’ tag. Authorities were shamelessly condescending towards Prof. Warrier, for his son was branded as a Naxalite, an anti-national of the highest kind. Media during that time, modulated and biased, and a sorry censored excuse for Press, was mostly antagonistic towards his struggle, and it was extremely difficult to gain a mass movement or even exposure for the excesses happening. He continued his indefatigable struggle by raising representations to President of India, Prime Minister and Home Minister of the time and to Members of Parliament, all with no result. He even appealed to general public by distributing pamphlets of his grievance, and Home Ministry retorted with a brand new excuse of murder accusation for Rajan being detained. Thanks to convoluted coalition politics, C. Achutha Menon’s communist cabinet in Kerala had K. Karunakaran, a staunch Congress leader as Home Minister; during Emergency. Prof. Warrier was a Communist sympathizer and had friendly connections with many ministers on a personal note. They avoided him for information that could easily have been obtained from subordinate officers, and finally deplored him when pleads became unavoidable. And the communist connection was used as another ploy by Police under Karunakaran to assert Rajan’s Naxalite involvement.

Rajan is said to have been a bright student, with active interest in music and drama. During the time of accused Police Station attack, he had an easily verifiable alibi at neighboring Ferok College, where inter collegiate arts fest was going on. Police never cared for any verification, and is said to have arrested him mistaking for another student by the same name. They were more interested in torturing conviction out of the ones they have in custody than capturing the actual suspects. Over the course of events, a lot of contradicting claims have been made by Police, from denying the arrest altogether to accusing Rajan of murder. Anyway accused was never brought in front of Magistrate. Speculated accounts of torture procedure and body disposal are mentioned in the book, it is blood boiling and heart breaking to read even if you don’t consider, about whom and by whom they were written.

By the later stages of his struggle, Prof. Warrier had accepted his Son’s death. Till then he had been vigorously searching central jails and police camps and all other sources he could obtain, physically, to see if Rajan had been kept in any of them. He was careful in keeping the truth off his ill wife, feeding her with lies about their son’s disappearance. Over the course of events, she broke down mentally, got hospitalized and eventually died of the pain, expecting Rajan’s return till her last breath. Eswara Warrier was a retired Hindi Professor, and the long search drained him heavily off money and health, but he kept pushing forward, learning the ways of court in his old age. He writes about the secret eleventh hour struggle to file habeas corpus, when news of Democracy restoration reached him, to escape possible political thread pulling. Unchained mass media was eager to carry the details of writ to public and the very first habeas corpus in history of Kerala gained huge crowd during court hearings. Police finally confirmed Rajan’s death in custody, K Karunakaran was forced to resign from the post of CM which he had pledged only two months before and DIG Jayaram Padickal was convicted and arrested. He later managed to overturn the conviction via appeal. Prof. Warrier continued his legal battle to expose the state sponsored atrocities during the Emergency period, and has been a significant figure in human rights till his death.

A striking feature of the book is Prof. Warrier‘s catholicity in reporting incidents of such personal trauma. He writes about it all, and pleads with readers, not to judge the people involved based on his remote experiences, for he has to write the truth. During his fight, he made serious effort to find out Rajan’s sentiment towards Naxal movement. Though he was never involved in, Rajan sympathized with the cause, and Warrier doesn’t hide this fact from readers. It takes real integrity and bravery to look for and admit even the smallest detail that could point towards the alleged accusation he fought so fervently against. He also mentions previous mental incidents his wife had. Though Rajan’s disappearance escalated her condition to death, Warrier doesn’t try to use it to strengthen his narrative. The compensation amount from case was directed to sponsor a critical care ward in Ernakulam General Hospital, in Rajan’s memory. Rest of the money was donated to University as youth festival endowments, to commemorate Rajan’s interest in arts.

I am reminded of a quote by Nehru here – “democracy and freedom are in grave peril today, and the peril is all the greatest because their so called friends stab them in the back“. And, we ourselves are more invested in the question of identifying the culprits – Indira Gandhi? Supreme Court of world’s largest democracy that conveniently complied for removal of habeas corpus with a majority of 4 against 1? Communal schism and violent naxalites? MISA? Press? Police? State Government? other et cetras? In this heated debate, often disregarded is the answer to an important question that goes unasked- the victims and their struggle. And the unasked question here is, who are and on what basis are they considered expendable in the mega narrative of democracy that we are so proud of.

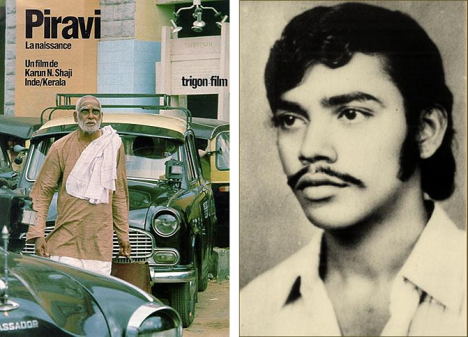

Rajan case has been the subject of many books and movies (Nation Award winner Piravi by Shaji N Karun for example) and passing references can be found in various popular mediums. This is because of the perseverance of his Father and his infallible belief in judiciary and constitutional methods as a citizen. Majority, if not all, of the excesses happened during National Emergency got drowned into oblivion over time, because of the censorship Press was subjected to. And then general notion was to overlook them as collateral damages. Sadly, this dangerous tendency is visible in modern democracy as well, where public opinion is often reduced into verbal squabbles over leaders and their ideology. Be it Emergency or Tribal evictions or recent Demonetization, general thought is either to gloriously condemn their political enemies or to find every probable reason, even if it defies ones conscience, to stand by their heroes. The expendable people who get disposed under the pretext of ‘for greater good’, like Arundhati Roy puts it, are rarely at the receiving end of our representation or even sympathy. Even when they are, they soon die once another fresh mishap, something our society aren’t short of, takes its place. And further from our safe vantage, we prioritize our sympathy in the ascending order of first world demographics. Where illogical blame games and subsidized morale cloud us from obtaining a sensible solution, this book is a reminder on how south things can go, when democracy and accountability fails. And that nobody is exclusive of it.

This book might not reach many people, for its written language- Malayalam(an English translation is available now, DRM free I believe), but nevertheless it is a struggle for democracy and fundamental rights against the autocracy and plutocracy it tend to get reduced to. Second part of the book gives details of Habeas Corpus with court case files and result, is a bit difficult to read with all the legal lingua-franca.

NIT Calicut‘s Art Festival – Ragam, one of the biggest of its kind in South India, is named and celebrated after the memory of P. Rajan. I have personally observed in great admiration, the ardent enthusiasm students share in upholding their erstwhile colleagues memory, which is preserved and remembered in due respect over academic generations.

————————————————————————————–

Emergency is a unique feature of Indian Constitution which covert federal structure into a unitary one where Central Government becomes all powerful, without a formal amendment of constitution. Three types of Emergencies are stipulated by Constitution

(1) National Emergency – war, external aggression, armed rebellion [Article 352]

(2) President’s Rule – failure of constitutional machinery in state [Article 356]

(3) Financial Emergency [Article 360]

Fundamental Rights will become suspended during the period (except those guaranteed by article 20 and 21), and State is free to take any legislative action abridging them. After the misuse of this provision during 1975, 44th amendment by Janata Government limited the power and nullified the distortions introduced previously. Emergency has been proclaimed three times so far- in 1962, 1971 and 1975.

In the forward, Naipaul identifies himself to be of the New World, having been raised in a far more homogeneous Indian community in Trinidad, than the isolated countrymen Gandhi met in South Africa in 1983. He also admits to have been washed clean off many religious attitudes, which according to him, are essential in understanding the civilization. This book is a collection of 8 essays in 3 parts, on his experiences and observations about the mainland, during Internal Emergency*(1975-1977).

In the forward, Naipaul identifies himself to be of the New World, having been raised in a far more homogeneous Indian community in Trinidad, than the isolated countrymen Gandhi met in South Africa in 1983. He also admits to have been washed clean off many religious attitudes, which according to him, are essential in understanding the civilization. This book is a collection of 8 essays in 3 parts, on his experiences and observations about the mainland, during Internal Emergency*(1975-1977).

The third essay – ‘The Skycrapers and the Chawls’, is Naipaul‘s ‘Maximum City’. His experiences in Bombay had made him render the city in an image of Dostoevsky’s St. Petersburg, but with a crowd that never truly dispersed. Unable to understand the prevailing street culture, he then goes back to the mistake of relating individual Identity with set of beliefs, and concludes that people are burdened with a nationalism, which, after years of subjection, badly demanded an Idea of India. This underlying narrative prevailed in the essay that followed where his definition of Naxalism is an intellectual tragedy of middle class, incapable of generating ideas of its own, borrowing someone else’s idea of revolution. His next essay, ‘A Defect of Vision’ tries to define Gandhian philosophy as a negative way of perceiving the external world. Naipaul argues Gandhi’s experiments and discoveries and vows as means for answering his own needs as a Hindu, for defining ‘the self’ in the midst of hostility, and not of universal application. He then puts forward an amazing review for U.R. Anantamurti’s novel, ‘Samskara’ to substantiate this fierce inward concentration of ‘hindu nationalism’. Gist of both could be better summed up in Sudhir Karkar’s words – “We Indians use the outside reality to preserve the continuity of the self amidst an ever changing flux of outer events and things”. I wish I could prove Naipaul wrong after what is almost half a century, but Indian Politics still remain narrow, and based on caste and religion as he accuses it to be, back then.

The third essay – ‘The Skycrapers and the Chawls’, is Naipaul‘s ‘Maximum City’. His experiences in Bombay had made him render the city in an image of Dostoevsky’s St. Petersburg, but with a crowd that never truly dispersed. Unable to understand the prevailing street culture, he then goes back to the mistake of relating individual Identity with set of beliefs, and concludes that people are burdened with a nationalism, which, after years of subjection, badly demanded an Idea of India. This underlying narrative prevailed in the essay that followed where his definition of Naxalism is an intellectual tragedy of middle class, incapable of generating ideas of its own, borrowing someone else’s idea of revolution. His next essay, ‘A Defect of Vision’ tries to define Gandhian philosophy as a negative way of perceiving the external world. Naipaul argues Gandhi’s experiments and discoveries and vows as means for answering his own needs as a Hindu, for defining ‘the self’ in the midst of hostility, and not of universal application. He then puts forward an amazing review for U.R. Anantamurti’s novel, ‘Samskara’ to substantiate this fierce inward concentration of ‘hindu nationalism’. Gist of both could be better summed up in Sudhir Karkar’s words – “We Indians use the outside reality to preserve the continuity of the self amidst an ever changing flux of outer events and things”. I wish I could prove Naipaul wrong after what is almost half a century, but Indian Politics still remain narrow, and based on caste and religion as he accuses it to be, back then. Remaining portions of book are more or less variegated accounts of Emergency Period, from freedom of Press to Poverty, with the underlying idea of ‘modernity’ or ‘Indian-ness’ being a facade. But he offered a brilliant perspective on Indian political programme being clamour and religious excitation. Gandhian-ism in modern day is reduced to Mahatmahood: religious ecstasy and self-display, and escape from constructive thought and political burdens. Like a solace for conquered people, alienated by the state, he argues. I thoroughly enjoyed his well researched last essay, where he criticized Bhave for overdoing everything and making Gandhi a figure like ‘Merlin’. Yet, by the end of the day, to Naipaul, India is without an ideology, locked in by fantasies of Ramraj(Rule of Ram: an Indian utopia), spirituality and return to village, where everyone is paralyzed with obedience as demanded by ‘dharma’.

Remaining portions of book are more or less variegated accounts of Emergency Period, from freedom of Press to Poverty, with the underlying idea of ‘modernity’ or ‘Indian-ness’ being a facade. But he offered a brilliant perspective on Indian political programme being clamour and religious excitation. Gandhian-ism in modern day is reduced to Mahatmahood: religious ecstasy and self-display, and escape from constructive thought and political burdens. Like a solace for conquered people, alienated by the state, he argues. I thoroughly enjoyed his well researched last essay, where he criticized Bhave for overdoing everything and making Gandhi a figure like ‘Merlin’. Yet, by the end of the day, to Naipaul, India is without an ideology, locked in by fantasies of Ramraj(Rule of Ram: an Indian utopia), spirituality and return to village, where everyone is paralyzed with obedience as demanded by ‘dharma’.